Tag: timeline

Vellum, Paper, and the Pencil

Vellum (5th century- 13th century)

Vellum (5th century- 13th century)

According to the New World Encyclopedia, “vellum is a sort of processed animal hide that is thin, smooth, durable and was used in the pre-printing age to produce written works in the form of a scroll, codex, or book”. Vellum is so durable, it is known to last for up to a thousand years, and thanks to this characteristic, we are able to continue to preserve and examine texts and works of art from medieval times. While it isn’t nearly as popular today among the general masses, vellum is still used for archival purposes for British Acts of Parliament and in the record keeping in the Republic of Ireland.

Vellum is produced by taking the skin of an unborn calf, traditionally, and having it soaked, limed, and scudded. Then, it needs to be stretched over a wooden frame until it is dry. All for one page to write on. The use of vellum meant the use of many, many calf-skins. The 12th century Winchester Bible is made up of more than 250 calf-skins, and that isn’t including any vellum pages that had imperfections in them (Lyons 22). In fact, the Gutenberg Bible had 30 vellum copies created through the use of over 5,000 calf-skins (Lyons 55). This would have been a timely and costly project, and it’s also an example of why vellum is hardly used at all today. But, it did indeed thrive in a society where writing wasn’t a common practice.

Paper (105 CE- present)

Paper (105 CE- present) The Pencil (1560’s-present)

The Pencil (1560’s-present)

Sometime in the 1560’s, a large graphite deposit was discovered in Cumbria, England by shepherds, who decided to dub the black substance “wadd” and brand their sheep with it. The wadd/graphite was noted for it’s superior line-making capabilities, erase-ability, and for the option to re-draw over top of it’s line with ink; something that couldn’t be accomplished with lead or charcoal. The graphite would also be mistakenly called “lead” due to great similarities between the two substances, even today. In fact, by 1610, strips of graphite wrapped in paper, string, or twigs called “black lead” were being sold in the streets of London. Due to it’s incredible popularity in 16th century Europe, it wasn’t long before the pencil began to be mass-produced with the first factory built in Nuremberg, Germany.

But, as the demand for pencils grew, control over the limited amount of graphite within Cumbria mine grew stricter, and people had to come up with alternate solutions. Some began to mix the graphite with other materials. In 1795 France, a man by the name of Nicolas-Jaques Conté decided to mix graphite with varying amounts of clay which would lead to the graphite grading scale with different degrees of hardness and blackness.

By 1866, after the pencil had made it’s way to America, Joseph Dixon, the owner of a pencil factory in Jersey City, decided to patent a wood-planing machine that would be capable of producing enough wood for 132 pencils per minute. Dixon would continue to improve upon his graphite mixing process up until 1873 when he began to market the pencil, as we know it today, as an American product and his factory as the “birthplace of the world’s first mass-produced pencils”.

Hieroglyphs, Papyrus and a LEAP to TEI

Ancient Hieroglyphs (3200 BCE- 1822 CE)

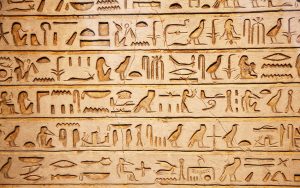

Hieroglyphic writing was a system invented and used by the ancient Egyptians. Hieroglyphs are the oldest examples of script to date. In the beginnings of this writing system, the Greeks and Egyptians believed hieroglyphics to be sacred text, a gift from God, hence, the name hiero for ‘holy’ and glypho for ‘writing’ in the ancient Greek language. In the ancient Egyptian language, hieroglyphs were called medu netjer, ‘the gods’ words’ (Scoville, 1). The script was created of three basic types of signs. Logograms represented words in the writing, while phonograms represented sounds. The third sign is called determinatives, placed at the end of the word to help clarify its meaning. Scoville explains that as a result of this systematic writing, Egyptians used over a thousand different hieroglyphs and during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE) the numbers of symbols used were reduced to about 750 (1).

The origins of hieroglyphs remain unclear. Some believed that the Egyptians learned to write from the Sumerians, who also began writing about the same time, about 3000 BC. However, the Egyptian hieroglyph does not look or work the same as the Sumerian form of writing, cuneiform (Carr, 1). The most popular hypothesis is that hieroglyphs derived from rock pictures dating back to prehistoric hunting communities in the dessert west of the Nile. It is believed that these prehistoric people were familiar with the concept of communicating by use of visual imagery. During the Naqada II period (c. 3500-3200 BCE), the motifs depicted on rock images were also found on pottery vessels of early Pre-dynastic cultures in Egypt. Hieroglyphic inscriptions are known to display stories of Gods, Demigods and half human half animal like figures, but they also contain inscribed numbers and mathematics. In fact, it is believed that the most complex inscription of administrative information related to economic activities was founded on pottery and stone vessels from tombs of Dynasty. This is the earliest recorded use of, what we would call, accounting data and taxation analysis for administrative purposes (Scoville, 4). Scoville goes on to explain the transition towards the Late Early dynastic (c. 3000 BCE), where examples of writing to commemorate royal achievements was found (5). In this case, hieroglyphic writing is found funerary stone and votive palettes, to honor the memory of the rulers and their achievements. The decline of Egyptian hieroglyphs took place during the Roman period (30 BCE- 395 CE) as Greek and Roman culture became more influential. Toward the second century CE, Christianity played a significant factor in the decline of hieroglyphs, as it displaced traditional Egyptian cults, making their system of writing obsolete.

The Papyrus Scroll (3000- 2890 BCE)

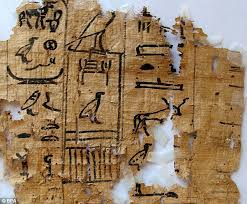

Papyrus appeared onthe scene during the First dynasty (3000- 2890 BCE), and became the most common source of portable writing in Egypt (Scoville, 3). Writng on clay tablets were quickly discontinued. What in the world is a Papyrus you ask? Papyrus is a plant that once grew, only, along the Nile River. Egyptians would cut the long papyrus stalks into thin slices and soak them in water and then stack them on top of each other in a weaving-like pattern. Then, they would pound the slices together until it created a flat material similar to paper. (Video: How to make papyrus paper) https://youtu.be/DCR8n7qS43w

Egyptians were the first to adapt this method of papyrus as a portable writing tool. By 1000 BC papyrus was in great demand because it was more convenient than clay tablets. This created great business as people from all over West Asia bought papyrus from Egypt. Since papyrus only grew in Egypt this particular item was in high demand. As a result, the price of papyrus was high. Around 700 AD the Islamic Empire learned from the Chinese how to make paper from rags from the, people quickly stopped using papyrus. Although the invention of paper from papyrus was short lived, it sparked the need for a portable writing system and revolutionized writing in terms of communication and how far information could go.

1987-2007

The TEI Consortium is a nonprofit membership organization composed of academic institutions, research projects, and individual scholars from around the world. Members of the initiative are responsible for maintaining a standard for representation of text in digital form. TEI consortiums follow a set of guidelines which specify encoding methods for machine-readable texts, mainly in disciplines such as the humanities, social sciences and linguistics. Before TEI creating sustainable and shareable textual material for archival and academia uses on a representing computer system was unheard of and not yet developed. This inhibited the development of the full potential of computers to support humanistic inquiry, while creating new problems for preservation and data sharing difficult. The TEI was originally developed maintain, and promulgate hardware- and software-independent methods for encoding humanities data in electronic form. TEI was a successful attempt to take on the challenges of digital technology. The goal of establishing the TEI Consortium was to maintain a permanent home for the TEI as a democratically constituted, academically and economically independent, non-profit organization. In addition, the TEI Consortium was intended to foster a broad-based user community with sustained involvement in the future development and widespread use of the TEI Guidelines. In both of these goals the Consortium has proven to be a positive step towards digital technology and communication as we know it, today. The TEI is internationally recognized as a critically important tool, for the long-term preservation of electronic data, and as a means of supporting effective usage of such data among many disciplines. TEI is the encoding scheme of choice for the production of critical and scholarly editions of literary texts, for scholarly reference works and large linguistic corpora (TEI: History, 4). The success of the TEI has catapulted our society in ways of ensuring that our cultural heritage will be brought forward into the emerging and forever changing, new world of technology.

Work Cited

Carr, K.E. “What is Papyrus?”What is Papyrus? – Ancient Egypt – Ancient Papyrus – Quatr.us. N.p., 01 Sept. 2016. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

Scoville, Priscila. “Egyptian Hieroglyphs.”Ancient History Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

TEI: Text Encoding Initiative.”TEI: Text Encoding Initiative. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

Folio (1400s-Present)

(youtube: Bindings)

Folio has a few different definitions. For one, it is a sheet of paper folded in half (Google Search). For our purposes, we will use the second definition: “an individual leaf of paper or parchment, numbered on the recto or front side only, occurring either loose as one of a series or forming part of a bound volume” (Google Search). In other words it is one or more fold sheets which have been bound together. Sounds a lot like a book doesn’t it? That’s why I am going to make the leap and say folios are still alive today.

The distinction must be made that folding, printing, cutting, and binding books is done with complex machinery today as opposed to how it was done long ago: by hand. See how it’s done today: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRKsW-oVcHg

It’s a little hard to determine when the very first folio was made, as folding a bunch of sheets of paper together and binding them is something that conceivably could have been done at any point in ancient history. Therefore, I will lighten my burden by beginning the history of the folio with the first printed folio, The Gutenberg Bible. The Gutenberg Bible, made in the 15th century, is “the world’s first book printed by movable metal type and hence the celebrated harbinger of the age of printing” (Robinson 513). Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the first moveable printing press ushered in the printing of unprecedented numbers of books.

One of the most important folios, called the First Folio, was compiled in the 17th century. The name is a little misleading, as the First Folio is not the first folio at all, but rather, the first folio to contain all of William Shakespeare’s printed plays. This folio was compiled by friends of Shakespeare, John Heminge and Henry Condell, in 1623–seven years after Shakespeare’s death. This compilation is particularly important, as Robinson notes: “Eighteen of the plays had been previously published in individual, small quarto editions, but the other eighteen, including Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and The Tempest, had never been printed and, but for Heminge and Condell’s volume, would have been forever lost.” (Robinson 513). This save alone, thanks to Shakespeare’s friends, is extremely clutch. Could you imagine a world with eighteen fewer Shakespeare plays? The only people to benefit from this would be students adverse to reading complex works of art.

Luckily, that was not the case. Shakespeare, just like folios/books in general, took over the world. To this day books in folio form remain the premier way to read lengthy works. Who’d want to read Harry Potter on the computer? Imagining scrolling through the entire series gives me the shudders.

Although folios have had a long history and will continue well into the future, the digital age is taking over. The age of printing is antiquated in the eyes of many and the storing of numerous print books is unnecessary. In fact, some libraries are so overstocked that they have begun destroying books (Licastro).

The printing of the folio ushered in the modern age (Robinson 520) and was the watershed moment that dealt the final blow to manuscripts. Printing reigned hundreds of years and still reigns. Now, however, with the advent of computers, we face another watershed moment–one which may see all publishing occur online, leaving the only existing works of print the works published today.

Sources:

Google Search. Google. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

HowQueue. “How Books Are Made – How Do They Do IT? (Printing Twilight Books).” YouTube. YouTube, 30 May 2013. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

“Making a Folio.” YouTube. YouTube, 09 Jan. 2016. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

Robinson, Fred C. “What Is a Rare Book?.” Sewanee Review, vol. 120, no. 4, Fall 2012, pp. 513-520. EBSCOhost. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

Creative Commons (2002-Present)

The beginning of Creative Commons is linked to Mickey Mouse (Geere). Just as the copyright for Mickey Mouse was about to expire, the U.S. government passed acts which extended the copyright. This happened like clockwork–during the 60s, 70s, and the 80s (Geere). In the 90s–1998 to be specific–the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act was passed, which extended copyrights another 20 years (Geere). Enter Eric Eldred. Eldred, a business owner who ran a website that reprinted works with expired copyrights, was clearly in danger. With Sonny Bono in place, Eldred saw that he would not have any new works to reproduce for the next 20 years (Geere). He decided to bring his case to court (Geere). Armed with a group of professionals, including an MIT professor and a Harvard staff-member, Eldred argued that the act was unconstitutional (Geere). The court case, and further appeals (even up to the Federal Supreme Court level), was lost (Geere).

The beginning of Creative Commons is linked to Mickey Mouse (Geere). Just as the copyright for Mickey Mouse was about to expire, the U.S. government passed acts which extended the copyright. This happened like clockwork–during the 60s, 70s, and the 80s (Geere). In the 90s–1998 to be specific–the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act was passed, which extended copyrights another 20 years (Geere). Enter Eric Eldred. Eldred, a business owner who ran a website that reprinted works with expired copyrights, was clearly in danger. With Sonny Bono in place, Eldred saw that he would not have any new works to reproduce for the next 20 years (Geere). He decided to bring his case to court (Geere). Armed with a group of professionals, including an MIT professor and a Harvard staff-member, Eldred argued that the act was unconstitutional (Geere). The court case, and further appeals (even up to the Federal Supreme Court level), was lost (Geere).

The group of professionals did not take this as defeat. They branded themselves Creative Commons and took matters into their own hands. The goal of Creative Commons was this: “The Creative Commons will provide a free set of tools to enable creators to share aspects of their copyrighted works with the public” (Geere). They made this known to the world with their 2002 press release, which also brilliantly said: “We stand on the shoulders of giants by revisiting, reusing, and transforming the ideas and works of our peers and predecessors” (Geere). Publicity was brought to Creative Commons because of its Supreme Court Case. Subsequently, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation donated $1,000,000 to Creative Commons which solidified the movement (Geere). By the next year, 2003, Creative Commons got access to one million works (Geere). As of 2011, Creative Commons has gained access to 350 million works (Geere).

The fight over the rights to one’s work spans back to year 561 in Ireland (Geere). Two saints, Columba and Finian, got into a feud over who had rights to the copies Columba made of Finian’s book (Geere). The feud was so intense that a battle was fought to determine who had copies’ rights (Geere). People died and Columba exiled himself from Ireland (Geere). In about a thousand years–with the invention of the printing press–printing companies had exclusive rights to whatever books it printed-rights neither public or even the author had (Geere)! The Statute of Anne act of 1709 remedied this issue (Geere). The act limited publishers’ rights to works to 14 years (Geere). As Duncan Geere puts it, The Statute of Anne “created the concept of a public domain for the first time, where the general public owns a creative work” (Geere).

Now, because of Creative Commons, art, science, and other forms of media are being made available for public use at an amazing rate. A new wave of creators are realizing there is more to be gained socially than financially by giving up their rights. This is happening all over the world, as Creative Commons intends.

This yields both good news and bad news. On one hand, more information is more accessible and more easily spread, which results in further remixing of works/information and more learning opportunities. However, as some photographers have noted, users can misinterpret or avoid the proper Creative Commons license on their works and use them for profit, without having permission. One photographer had this to say:

“The CC standard says that photographers should get credit, but I discovered that I was not being credited and that there were occasions when the photos were being ascribed to other photographers. On another occasion I found an all rights reserved copyright photo being used. It had been taken from Flickr. The photo was removed and the people who took it told me that they thought it was available for use, even though it was marked. There are people out there who think Flickr equals free to use.” (Scott).

Thus in a world that’s becoming Creative Commons friendly, it is still in the creator’s best interest to make sure their work is licensed correctly (Bert-Erboul).

Sources:

Bert-Erboul, Clément. “The Creative Commons . A third way between public domain and community? “, Sociological and Anthropological Research. 2015. online 21 April 2016. Web. Accessed 24 February 2017.

Geere, Duncan. “The history of Creative Commons.” WIRED UK. WIRED UK, 22 May 2016. Web. 24 Feb. 2017.

Scott, Katie. “What does Creative Commons mean for photography?” WIRED UK. WIRED UK, 23 May 2016. Web. 24 Feb. 2017.

Randell, John. Creative Commons logo, 3 Mar. 2010. Web. 24 Feb. 2017.

The Republic of Letters (1685-1850)

The Republic of Letters (1685-1850)

A network of letters through Europe and America was created for philosophers and scholars to share their concepts with each other. The Age of Enlightenment brought in a system would evolve into newspapers and academic journals expanding languages and culture.

Not only did it transcend language in culture, but it brought like minded individuals together into schools and universities out of France. It is hard to know where exactly the sharing of letters started, but we do know France was in the center of it (History.com,”Enlightenment”).

The Republ ic of Letters can sometimes be called the men of letters because society refrained women from participating. That did not mean however, that there were not many important women figures who were a part in the age. Salons played a pivotal role in not only bringing together intelligent individuals to educate one another, but they established order and a civil space. One salon owner was Marie-Therese Geoffrin. Her establishment became well known and most frequented as she held weekly dinners from 1749 until her death in 1777. She had inherited the salon from Madame de Tencin, who was more unconventional compared to Geoffrin who wasn’t formally educated, but had natural intelligence. Marie-Therese Geoffrin strict rule during her occasions was no talk of politics or religion. The host and hostesses of the salons were very respected among the “Men Of Letters”, it didn’t also allowed for their reputation to grow if they received enough praise (“The Kingdom of Politesse”).

ic of Letters can sometimes be called the men of letters because society refrained women from participating. That did not mean however, that there were not many important women figures who were a part in the age. Salons played a pivotal role in not only bringing together intelligent individuals to educate one another, but they established order and a civil space. One salon owner was Marie-Therese Geoffrin. Her establishment became well known and most frequented as she held weekly dinners from 1749 until her death in 1777. She had inherited the salon from Madame de Tencin, who was more unconventional compared to Geoffrin who wasn’t formally educated, but had natural intelligence. Marie-Therese Geoffrin strict rule during her occasions was no talk of politics or religion. The host and hostesses of the salons were very respected among the “Men Of Letters”, it didn’t also allowed for their reputation to grow if they received enough praise (“The Kingdom of Politesse”).

These salons were a part of high society, making it possible for men to have their work be protected. Patronism and clientelism allowed for different things depending on the person. A client only institutionalized a bond between an author and a great noble depending on the political belief or literary service. A patron was eligible to receive awards and gifts. The system is different between salons, but the gifts weren’t because of specific works, they were more of a generous token of friendship. The gratitude towards one another helped solidify protection, all out of the polite nature of others (“The Kingdom of Politesse”).

The invention of printing press established communities of philosophers and scientist who were now able to communicate new ideas and discoveries through journals. These journals gave the Republic of Letters more attention as the public became more interested in the content. The ideals of the men would be published in their journals, along with debates, information, and later taking over as a primary news source (Wikipedia,”Republic of Letters”).

“The Republic of Letters” in France and England had much influence on American letters. Many of their ideas had not existed in America, for the most part, the only way to keep the intellectual philosophies alive was to report on literature (“Republic of Letters”). The impact it had allowed for a new form of communication between individuals who needed an outlet to have intellectual conversations and grow their own knowledge. All while also educating the public on different matters of thinking.

Works Cites

“Republic of Letters.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 07 Feb. 2017. Web. 21 Feb. 2017.

History.com Staff. “Enlightenment.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, 2009. Web. 24 Feb. 2017.

“The Kingdom of Politesse: Salons and the Republic of Letters in Eighteenth-Century Paris.”ARCADE. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2017.

Photo

Lemonier Gabriel-Charles, Anicet. “A Reading in the Salon of Mme. Geoffrin.” Wikimedia Commons, 6 April 2009 Web. Feb 24. 2017

The Codex (200 – 1500 A.D.)

The codex is the predecessor to what we would all recognize as a modern book. It replaced the scroll in ancient times as the main source of information storage. The movement from scroll to codex to book was fairly natural and intuitive as each new technology used the same materials as the previous, only improved production, usage and accessibility.

One of the biggest improvements the codex offered over the scroll is its ability to allow “random access”. This means you can open up the codex to any point or page and begin reading. Scrolls did not allow random access and forced readers to begin at the point where the scroll was last rolled up to, usually the start (Dykes). To find information the whole scroll had to be unrolled and then gone over. Codices also took up much less room than scrolls, which in addition to being slow to use were bulky and delicate. The codex eliminated this tedious process and made information easily and quickly accessible (Dykes).

A codex is usually made of thicker material than the paper of a modern book. Usually papyrus, vellum or an earlier paper would be used depending on what era the codex was made in. Several styles of codex exist and have been found all over the world. Most had pages that face each other just like a book and most codices featured a spine. Some codices, usually the earlier ones, folded out accordion style or featured panels like the one pictured above (Frost). While not as easy to use or read as a codex with a spine, these fold-able manuscripts still were a massive improvement over scrolls and still allowed for random access.

The exact time that the modern book replaced the codex is a fuzzy area as technically a paper-back book is still a codex. Some definitions of a codex require the text to be handwritten still (manuscript), I like that definition and think its the easiest to understand when comparing codices to modern books. Sometime around the beginnings of the first printers and thinner paper, the codex was fazed out and replaced by the modern style book. (Norman)

Consistent with the time in which they were developed, many of the first codices contained religious information. Various cultural renditions of the bible have been historically preserved in codices and have proved useful for historical and academic studies. (Frost) Religious groups were quick to adopt codices because of their convenience, portability and versatility. Illustrations and text were both able to be added to pages and easily shown to audiences or congregations and the ease-of-use allowed for the codices to be easily handled or distributed. Right around the same time the codex was invented, Christianity began to spread across the middle east. The new religion adopted the codex in the form of its bible and is largely responsible for transporting the codex along with the knowledge regarding how to produce them across their region (Dykes).

Sources:

Frost, Gary . “Adoption of the Codex Book: Parable of a New Reading Mode.” [CoOL]. N.p., 3 Aug. 2003. Web. 23 Feb. 2017. http://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v17/bp17-10.html

Dykes, Victoria. “From Scroll to Codex: A Religious and Practical Transition (Victoria Dykes ’13) – From Tablet to Tablet: A History of the Book.” Google Sites. N.p., 2013. Web. 23 Feb. 2017. https://sites.google.com/a/umich.edu/from-tablet-to-tablet/final-projects/-victoria-dykes-13

Norman, Jeremy. “The Transition from the Roll to the Codex: Technological and Cultural Implications.” The Transition from the Roll to the Codex: Technological and Cultural Implications. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Feb. 2017. http://www.historyofinformation.com/narrative/roll-to-codex.php

Image:

Tilford, Charles. Mayan Dresden Codex. 2012. Flickr. Web. 23 Feb. 2017.

Quill Pen, Copyright, and Project Gutenberg

Quill and Ink

The earliest form of writing that is closest to the pen and paper we have today was developed by the Greeks (Bellis). They created writing styluses out of bone, metal or ivory, predating the quill by about 200 years. The quill was introduced in about the year 700 CE and dominated the writing scene for thousands of years (Bellis). The quill is made from a bird’s feather and is strongest when plucked while the bird is alive. Typically, the feather is plucked from a “robust bird” (Tillotson) such as a goose. The left wing of the bird was favor because the curvature of the feather was more ideal for a right-handed person (Bellis). A good quality quill can be used for about a week before it must be replaced and must be sharpened by a special knife, this is where the term pen-knife comes from (Bellis).

The make the pen “it was usual to cut back the plume of the feather and remove the barb, or feathery bits” (Tillotson). This process makes the quill easier to write with and hold. The quill was then placed in hot sand to strengthen the barrel and a pen-knife was used to remove the point (Tillotson). This allowed the scribe to hollow out the inside of the quill and sharpen the nib. The quill was very fragile and became dull easily, which was an issue when the quill was first invented because of the expense of vellum.

Ink was invented by a Chinese philosopher and by 1200 BCE was a common place item in the world. Originally ink was made from the ashes of pine needles, lamp oil, and a gelatin mixture from donkey skin (Bellis). A more stable ink compound was later invented, made from composites of iron-salt, nutgalls, and gum.

The impact made by the invention of the quill and ink can still be seen today. The invention of the Greek styluses, Roman reeds, nibs, and quills ran parallel to the invention of paper. As paper quickly changed and become more commonplace, simpler writing implements were created. The quill was invented in response to the invention of fibrous paper in China which was easier to make and less expensive than vellum and animal skins. Once paper became more easily accessible, people needed a faster, more reliable implement to write with. As paper processes were perfected and paper was made widely available around the 14th century by paper mills in Europe, the art of writing with a quill became more wide spread and easily accessible to the general population. The mechanics of the quill have been perfected and were eventually replaced with a more sturdy and trustworthy implement, the steel nibbled pen (Tillotson) around 1822 (Quill Pen [00:00:19]). By the 1800s education rates had also increased significantly and more convenient forms of writing were needed which led to the steel nibbled pen and more stable ink. The modern-day ball-point pen still uses many of the same mechanics as the quill pen, with a longer life span, varieties of ink colors, and better reliability.

Work Cited:

Bellis, Mary. “A Brief History of Writing.” About, 13 Aug. 2016, inventors.about.com/od/timelines/fl/A-Brief-History-of-Writing.htm. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Quill Pen: How to Make Everything: Book. Produced by Andy George, YouTube, https://youtu.be/eDbtJOjFv7s, 2015.

Ashreila, Writing, Nov. 17, 2015, accessed Feb. 23, 2017

Tillotson, Dianne, Dr. “The Quill Pen.” Medieval Writing, 11 July 2011, medievalwriting.50megs.com/tools/quill.htm. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Copyright

Copyright issues became a problem as printable media became widespread. Without any laws to protect information, anyone could claim that your book was theirs or your research was their research. Copyright laws have changed the way we can use information and was made significant “by waves of innovation in information technology” (Jaszi). Though the creation of the law was not in response to technology but driven by “social life, economic organization, and cultural outlook” (Jaszi).

Britain was the first to propose a law to protect information with the Statute of Anne. The Statute of Anne was first put into law in 1710 (Jaszi), it was the first law of its kind which became standardized and made international. The statute guaranteed authors of new books a “copyright of fourteen years from publication” (Gomez-Arostegui [Pg. 1249]). It was also the first law of its kind to recognize that by creating a way to protect published information, it would encourage people, especially scientists and artists, to publish their work, thereby growing the industry.

The Statute of Anne inspired the US to create the Copyright Act of 1790 stating that “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” (Katz). The US granted authors the right to print, reprint, and publish their work for fourteen years and renew for another fourteen (Katz), which, like the Statute of Anne, was designed to give authors, artists, and scientists incentive and limit their monopoly on the information.

The Statute of Anne and the Copyright Act of 1790 only protected the authors of those countries. In 1891, the International Copyright Act of 1891, more commonly known as the Chace Act, began the process of providing foreigners protection, it provided that “so long as they complied with the US notice, registration, and deposit of requirements” foreigners could obtain US copyrights for their work (Nimmer).

Originally, copyright laws were used for incentive but today, copyright law “has now become a suit of nearly impenetrable armor that allows copyright-holders to block new works from entering the culture and to dictate how older works fit into our cultural framework” (Hlinak). People use copyright to hold a monopoly over a particular idea, character, or plot. Today, we see this with many of the superhero movies.  Now that DC and MARVEL have become popular in not only comics but movies and TV, the companies are buying back the rights to certain characters that they once sold, such as MARVEL selling Spiderman to Sony. It has taken years for them to regain the copyright over the character and they are only regaining it due to the copyright expiring. Another place we see copyright blocks is for marching bands. Bands have to buy the rights to the songs they use and this can cost thousands of dollars. This makes it difficult for bands with small budgets to succeed. This also becomes an issue when looking at Fandoms. Fandoms create artwork, fanfiction, and alternative universes using characters from books, movies, and TV, copyrights certainly come into question when we look at these and authors/artists must put disclaimers on their work to protect themselves.

Now that DC and MARVEL have become popular in not only comics but movies and TV, the companies are buying back the rights to certain characters that they once sold, such as MARVEL selling Spiderman to Sony. It has taken years for them to regain the copyright over the character and they are only regaining it due to the copyright expiring. Another place we see copyright blocks is for marching bands. Bands have to buy the rights to the songs they use and this can cost thousands of dollars. This makes it difficult for bands with small budgets to succeed. This also becomes an issue when looking at Fandoms. Fandoms create artwork, fanfiction, and alternative universes using characters from books, movies, and TV, copyrights certainly come into question when we look at these and authors/artists must put disclaimers on their work to protect themselves.

Work Cited:

Gomez-Arostegui, H. Thomas. “The Untold Story of the First Copyright Suit under the Statute of Anne in 1710.” Berkeley Technology Law Journal, vol. 25, no. 3, June 2010. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1853&context=btlj. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Jaszi, Peter, et al. “The Statute of Anne: Today and Tomorrow.” Houston Law Review, vol. 47, no4, Dec. 2010, pp 1013-1021. EBSCOhost. Exproxy.stevenson.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&an=59250718&site-eds-live&scope=site

Katz, Stanley, editor. “Copyright Timeline: A History of Copyright in the United States.” Association of Research Libraries, 2014, www.arl.org/focus-areas/copyright-ip/2486-copyright-timeline#.WK8wOlXyvIU. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Nimmer, David. “Nation, Duration, Violation, Harmonization: An International Copyright Proposal for the United States.” Duke Law, 21 Mar. 1991, scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4145&context=lcp. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Hlinak, Matt. “The Impact of Modern Copyright Law on the Creation of Derivative Literary Works.” Review. Communication Law Review, Northwestern University, 14 May 2006, commlawreview.org/Archives/v8i1/The%20Impact%20of%20Modern%20v8i1.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb. 2017.

Marvel Studios Logo. JPG file.

Seyfang, Mike. Copyright. 11 Nov. 2008, JPG file. Accessed 28, Feb. 2017.

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg was the first provider of free electronic books (ebooks) created in 1971 by Michael Hart. It was used to encourage the creation and distribution of ebooks. The idea behind Project Gutenberg was the idea of “Replicator Technology”, which essentially means that once a book is on line, it can be replicated as many times as need demands, creating an infinite supply of that book and can be stored anywhere (Hart). The ebooks created by Project Gutenberg are made in the most simple forms to use and are readily available, which allows for any device to run and search the files.

Texts are made to be 99.9% accurate, according to Hart, and does not create authoritative editions of the texts and editing is up to the preferences of the proofreaders (Hart). It is more important to create something easy to use that everyone has access to than to create something completely accurate.

Project Gutenberg’s philosophy of “Replicator Technology” has become wide spread. Amazon, Barnes and Nobel, and other companies have taken advantage of this idea to create an infinite supply of books and media for people to use and enjoy. This idea has become so popular that we now have audiobooks available the same way, both abridged and unabridged. Hart’s philosophy has also expanded into music where we now have programs like iTunes, Spotify, and other programs that allow people access to thousands of artists and albums. While not all of these are free to use, many offer “discounted” prices on their products.

With the invention of eBooks, copyright laws have become somewhat easier to manage. Copyrights must be filed with the US Copyright Office, paperwork must be filled out, and a fee must be paid (Lovett). The danger of eBook publishing is people impersonate original authors and publish their work as their own. Originality is easy to prove with word processors which give the exact time and date stamp of the original document.

Works Cited:

Hart, Michael. “The History and Philosophy of Project Gutenberg.” Project Gutenberg, 7 Apr. 2010, www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Gutenberg:The_History_and_Philosophy_of_Project_Gutenberg_by_Michael_Hart. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Lovett, Anita. “When to Copyright your eBook.” Anita Lovett & Associates, 18 June 2015, anitalovett.com/2015/06/18/when-to-copyright-your-ebook/. Accessed 28 Feb. 2017.

Sauers, Michael. Project Gutenberg, 26 Aug. 2014, JPG file. Accessed Feb. 23, 2017

Movable Type (1041-1884)

Movable Type (1041-1884)

The impact movable type had on the writing process changed the amount of writing that can fit on paper; thus improving the rate of communication. Both the Koreans and Chinese discovered wood block painting around the mid 900’s out of wood and clay. The mass production of books became big even before the printing press because Korea was transitioning into Buddhism during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). Religious readings of the “Tripitaka” (“Short History of Asia’s Influence on Type and Printing”) that included sutras, treaties, and laws, made it essential to create 2 complete sets. China first used movable type in the 11th century but never was really used. Created by Bi Sheng, characters were made out of clay until the mid 13th century, moving to movable wooden type. The many characters of the Chinese alphabet however, made it less expensive to use wood. By now the Europeans had perfected a much more effective method of movable type (“Short History of Asia’s Influence on Type and Printing”).

In 1450, Johannes Gutenberg created the printing press. His creation revolutionized movable type. Gutenberg made his tiles out of metal casting, formulated with tin, lead, pewter, and later adding antimony. Making these pieces unfortunately was no task for any ole person. They relied on experienced goldsmiths (like Gutenberg) to create the three main types, the “Punch, Matrix, and Mold” (“Gutenberg and His Movable Type Process”).

The punch was a metal rod with the letter carved backwards to be driven into the matrix, which was a softer piece of metal. The matrix was then placed into the mold, being filled with hot liquid metal, quickly hardening into a type piece. The punch and matrix would be reused so they ended up creating identical characters. The method would then be called the “Punch Matrix System” (“Gutenberg and His Movable Type Process”).

Movable Type lasted for about 400 more years until the invention of hard metal typesetting. Movable type began to decline, but it’s impact on print and the ability to put out more information in a faster process created ideas for many of the technology in today’s world.

Works Cited

“Johannes Gutenberg: The Invention of Movable Type.” Johannes Gutenberg: The Invention of Movable Type. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2017.

“Short History of Asia’s Influence on Type and Printing.” Elation Press. N.p., 09 Aug. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2017.

“Gutenberg and His Movable Type Process.” Gutenberg and His Movable Type Process. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Feb. 2017.

“Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.” Harry Ransom Center. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Feb. 2017.

Photo

Vinne De Low, Theodore. De Vinne 1904-Punch and Matrix, 1904, Web Feb 23, 2017

Time Line: – Newspaper – Steam Press – Windows –

Each of these inventions have become intricate parts of society and have had dramatic impact on the way people receive media. Either they’ve died down in recent years, or are continuing to expand, each of these publication methods have reached millions of people worldwide.

Newspaper dates back to ancient dynasties in China, where they would use block printed into paper and this occurred during the Tang dynasty. Since then, with the invention of the printing press in 1440, newspaper made its day view in Strasbourg Germany. What was then, the Holy Roman Empire. In 1605 Johann Carolus began printing what would later be credited as the first ever official newspaper, “Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien.” This was a news publication and has influenced the way people tell the news since its start. The printing press was the direct cause of newspapers and they were bound to come into existence as long as printing methods became easier and easier to mass produce large quantities of papers. This helped develop a need for average citizens to at least be able to read. That way they could keep up with the biggest new stories and keep in touch with whats happening in their nation. This is the first time where something that happened yesterday, possibly even in another country, would then reach a commoners doorstep and inform them of the things going on in the world. It was an extremely empowering tool and one that became widely popular. It took less than a hundred years for it to spread across the world to the Atlantic ocean and then eventually into Asia.

Steam Press. This invention goes hand in hand with the Newspaper. In 1810, Friedrich Koenig invented the first steam printing press. This allowed for rapid printing and for daily newspapers rather than weekly copies. The machine was a simple hand press machine made of cast iron, but simply hooked up to a steam press for faster printing. The steam engine, a brand new invention at the time, was being implemented in every form of machinery. Steam engines were attached to many numbers of gadgets to improve efficiency and made life much easier for many Americans. This era is also what many video games refer to as Steampunk. Everything was adapted to fit steam engines (Geoghegan). This phase in history didn’t ignore the printing press. The steam powered rotary printing press was made in the United States in 1843 by Richard M. Hoe. Mr. Hoe revolutionized the industry by adding a rotary press into the mix. The cylinder which replaced the common flat press, started to churn out numerous copies and massive amounts of paper. He tripled the output of the average flat printing press. It allowed millions of copies to be run in a single day.(Moore) This opened up news channels like never before and inspired reading and writing among all social classes.

Jumping ahead to Windows. Windows is the most common operating system in computers worldwide. Made by Bill Gates and his Microsoft team back in 1985. Windows was designed as a simple graphic interface and wouldn’t become a hit until Windows 3 in 1990(Fitzpatrick). This was also the birth of the Word document. This interface allowed for people to create text documents and a number of features, never before seen. This interface opened up and made the creation of printable documents considerably easier for anyone with a computer. Handwriting was no longer an issue and printing became more easily accessible. Windows continued to evolve as a operating system. The operating system(OS) is what everyone is familiar with today. The OS simplifies coding and command functions in computers. The OS basically over simplifies the use of a computer for average people without computer experience. Some of the backlash involved with this is the complaint that people won’t understand the coding involved with the creation and functions of a computer. While this is true, it allowed for computers popularity to hit mainstream with large companies pushing OS’s forward. Such as IBM and Microsoft.

- Cory Price

Newspaper

Steam Press

Windows Logo

Works Cited

Bgfons. bgfons.com/download/2828. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

DiBacco, Tomas V. “Banned in Boston: America’s First Newspaper.” Wall Street Journal – Eastern Edition, vol. 266, no. 73, 25 Sept. 2015, pp. 1-6. Academic Search Complete, web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=5&sid=95b9c901-9284-475d-bfdb-165a495def2b%40sessionmgr4009&hid=4204&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=109932474&db=a9h. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

Fitzpatrick, Alex. “It Took Microsoft 3 Tries Before Windows Was Successful.” Time.Com, 20 Nov. 2014. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.stevenson.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=99555396&site=ehost-live.

Moore, Keith. “Rolling Thunderer.” Professional Engineering, vol. 13, no. 22, 29 Nov. 2000, p. 65. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.stevenson.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=3945617&site=ehost-live.

Teleanalysis. www.teleanalysis.com/news/microsoft-christmas-gift-windows-fans-india-23958. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

WordPress.aehistory.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/screen-shot-2012-10-08-at-1-12-36-am.png?w=298. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.